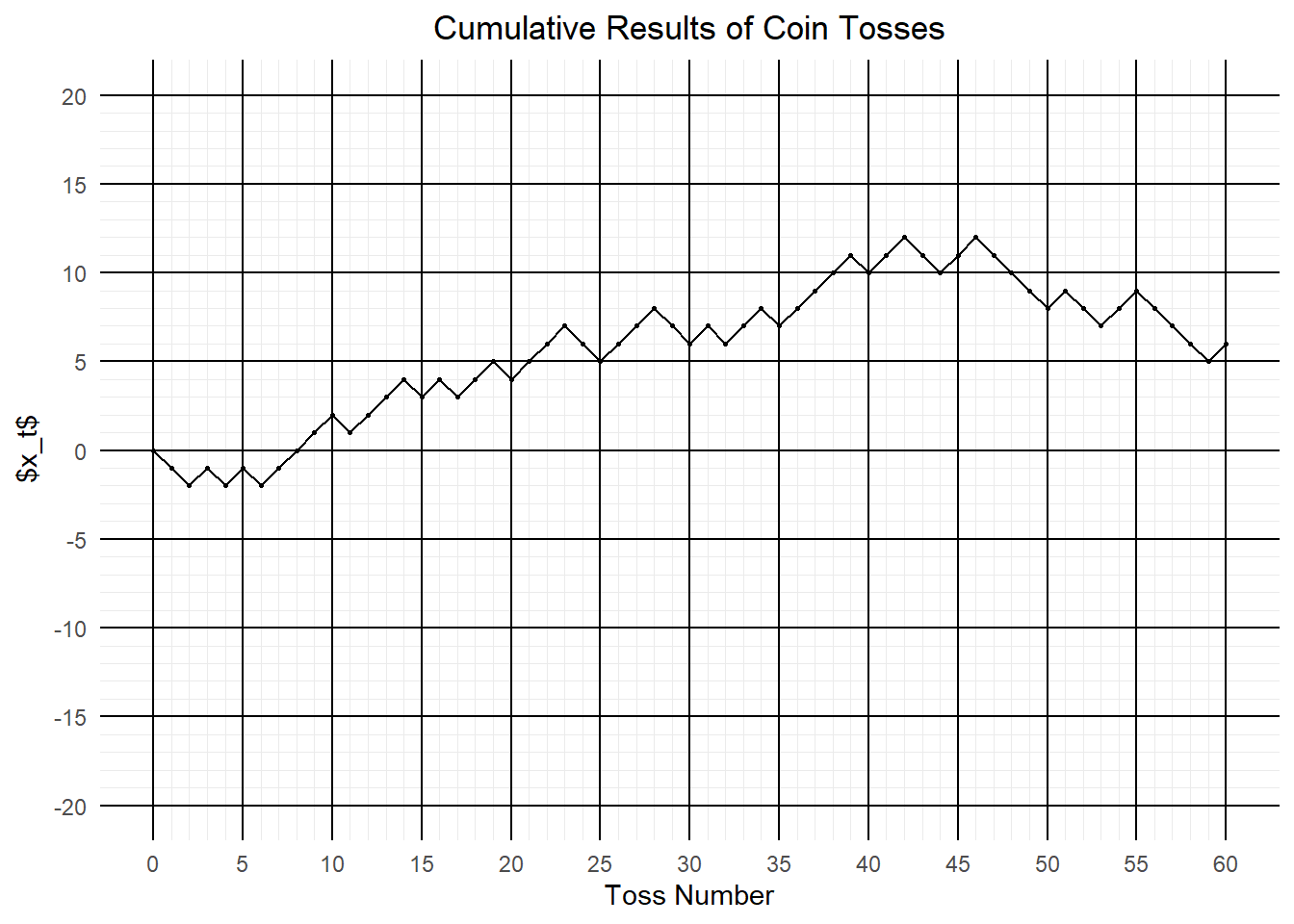

Why is \(cov(x_t, x_{t+k}) = t \sigma^2\)?

First, note that that since the terms in the white noise series are independent,

\[

cov ( w_i, w_j ) =

\begin{cases}

\sigma^2, & \text{if } ~ i=j \\

0, & \text{otherwise}

\end{cases}

\]

Also, when random variables are independent, the covariance of a sum is the sum of the covariance.

Hence, \[\begin{align*}

cov(x_t, x_{t+k})

&= cov ( \sum_{i=1}^t w_i, \sum_{j=1}^{t+K} w_j ) \\

&= \sum_{i=j} cov ( w_i, w_j ) \\

&= \sum_{i=1}^t \sigma^2 \\

&= t \sigma^2

\end{align*}\]