Confidence Intervals for a Mean

Introduction

Lesson Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Recognize when a one mean (sigma known) confidence interval is appropriate

- Explain the meaning of a level of confidence

- Create a confidence interval for a single mean with

- Find the point estimate (

- Calculate the margin of error for the given level of confidence

- Calculate a confidence interval from the point estimate and the margin of error

- Interpret the confidence interval

- Check the requirements for the confidence interval

- Find the point estimate (

- Explain how the margin of error is affected by the sample size and level of confidence

Statistical Inference is the practice of using data sampled from a population to make conclusions about population parameters.

The two primary methods of statistical inference are:

- Hypothesis Testing

- Confidence Intervals

This chapter lays the foundation for confidence intervals.

Background

Point Estimators

We have learned about several statistics. Remember, a statistic is any number computed based on data. The sample statistics we have discussed are used to estimate population parameters.

|

Sample Statistic |

Population Parameter |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Mean |

|

|

|

Standard Deviation |

|

|

|

Variance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The statistics above are called point estimators because they are just one number (one point on a number line) that is used to estimate a parameter. Parameters are generally unknown values. Think about the mean. If

The short answer is that we will never know for sure if

Review: Distribution of Sample Means

Confidence intervals rely on the validity of the assumption that the distribution of the sample mean is normally distributed.

Recall that the distribution of sample means is normal when:

- The underlying population is normally distributed

- The sample size, n, is sufficiently large (

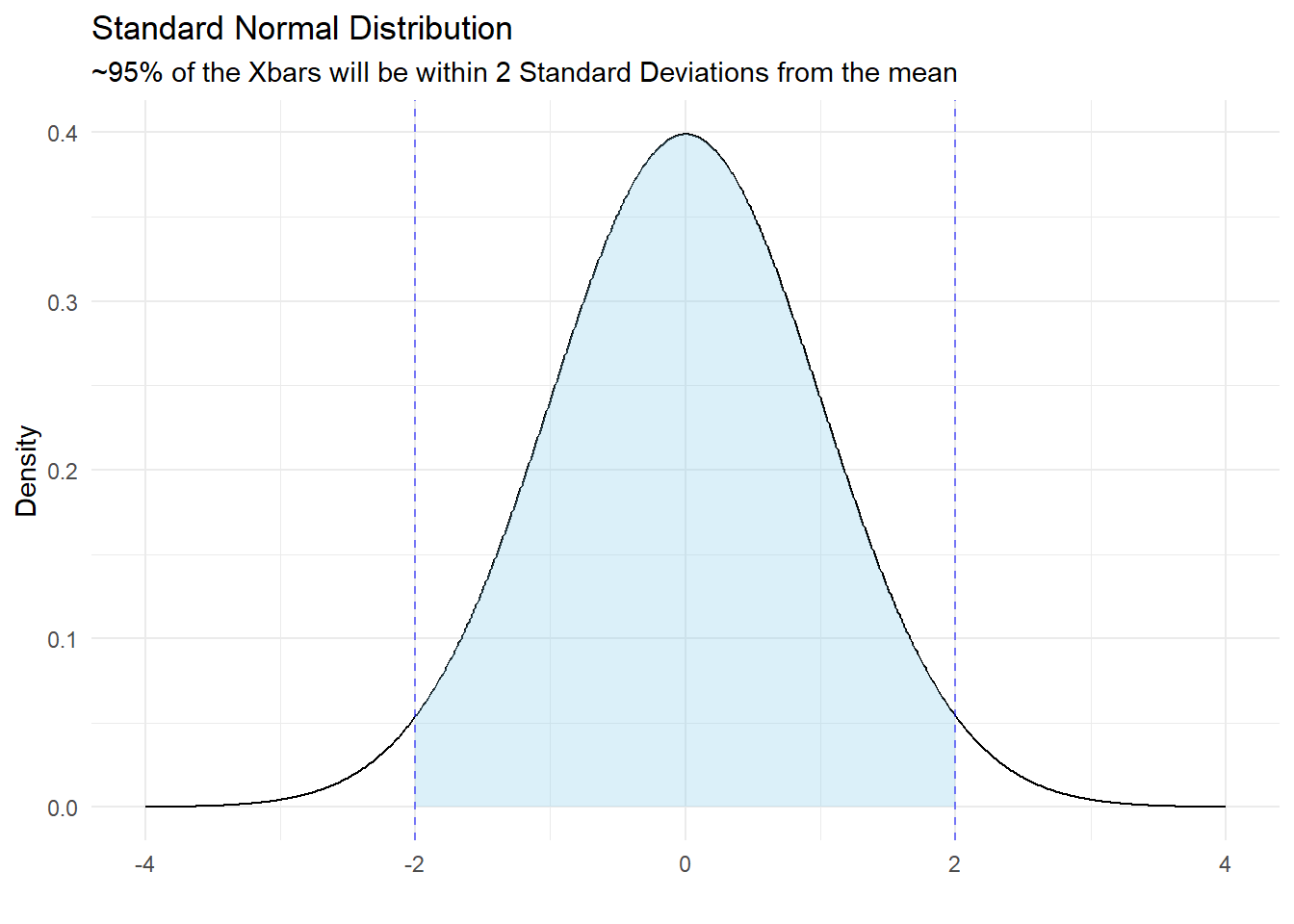

Thought Question: If we have a good sample from a population and can trust that the sampling distribution of the mean is approximately normal, how frequently would a sample mean be within 2 standard deviations from the true population mean?

Remember, the standard deviation of

ANSWER: If we collect a random sample from a population and

This means the 95% of the time, we will get a sample mean within 2 Standard Deviations of the true population mean.

Flipping this around, if we take our sample mean and make an interval 2 standard deviations above the mean and 2 below, the interval will overlap with the true population mean about 95% of the time.

An Approximate 95% Confidence Interval

The equation of an approximate 95% confidence interval would be:

The part that we are adding and subtracting from our point estimate is called the Margin of Error. We use the letter

Using this definition for

Confidence Intervals

Recall that it is only approximately 95% of the area under the curve within 2 standard deviations of the mean.

We want to be more precise in our confidence intervals and may want to choose a level of confidence different from 95%.

The generalized formula for a confidence interval is

Where

Common

| Conf. Level | Z* |

|---|---|

| 0.99 | 2.576 |

| 0.95 | 1.96 |

| 0.9 | 1.645 |

Confidence Level is related to the probability of a Type I error,

A 95% confidence interval will miss the true population mean 5% of the time because 5% of the time you will get a mean in the one tail or the other of the sampling distribution just by chance.

Interpretation

Confidence intervals are typically reported using parentheses like: (lower limit, upper limit). We say that we are

Average GRE Scores of BYU-I Students

The published population standard deviation of the quantitative portion of the Graduate Record Examination (GRE) scores is

Suppose we take a random sample of

We can calculate the 99% confidence interval:

The interpretation of the above confidence interval would be:

I am 99% confident that the true population mean GRE score for BYU-I students is between 159.96 and 164.24.

Relationship to Hypothesis Testing

Consider that the published population mean for GRE test-takers if 158.

QUESTION: Does the true population mean of all test-takers fall inside our confidence interval?

Because 158 falls below our confidence interval, we conclude that BYU-I students score higher, on average, than the general population with 99% confidence.

Margin of Error

QUESTION: What happens to the margin of error,

QUESTION: What happens to the margin of error,

Consider that if I make a wide enough interval, I can be 100% confident. But to get 100% confidence, my interval will be useless. For example, I can be 100% confident that the true population averge height of BYU-I students is between 2 feet and 100 feet. More confidence means we need a wider interval.